Photo credit: ResoluteSupportMedia, “101219-F-3682S-296,” Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

In this section, we sketch the two key interrelated sets of protections under IHL for impartial medical care in armed conflicts involving terrorists. The first set involves the entitlement to and the protection of medical care for the wounded and sick hors de combat. As a corollary to the first, the second set encompasses the most salient protections for medical caregivers, transports, units, and supplies. Within each of these main sets of measures, we highlight the most important subsidiary categories of protection.

This section is meant to be a primer: it focuses on the most salient aspects of IHL protections for impartial medical care concerning terrorists.[1] We do not raise or address other elements of protections for impartial wartime medical care—and there are many. They range from identification standards for medical aircraft to provisions on establishing hospital and safety zones. Nor do we examine protections falling under the broader umbrella of humanitarian relief and assistance, including medical supplies.

The upshot of our analysis is that because there is no specific status of “terrorist” in IHL, the protections for impartial medical care concerning terrorists largely turn on those persons’ status under the relevant source of IHL. And the specific medical-care protections that attach to a particular status track the more general fragmentation between states and across types of armed conflict. However, as a general matter, where they do exist, none of the identified IHL medical-care protections is limited—in any way—due to involvement in terrorist acts or a terrorist designation.

Discerning the scope of medical-care protections under IHL for a specific person fighting in or (otherwise) affected by an armed conflict involving terrorism may turn on such factors as:

- Her status, tasks, and/or functions under IHL;

- The category of armed conflict: an IAC or a NIAC;

- The applicable treaty (or treaties); and

- The applicable rule(s) of customary IHL.

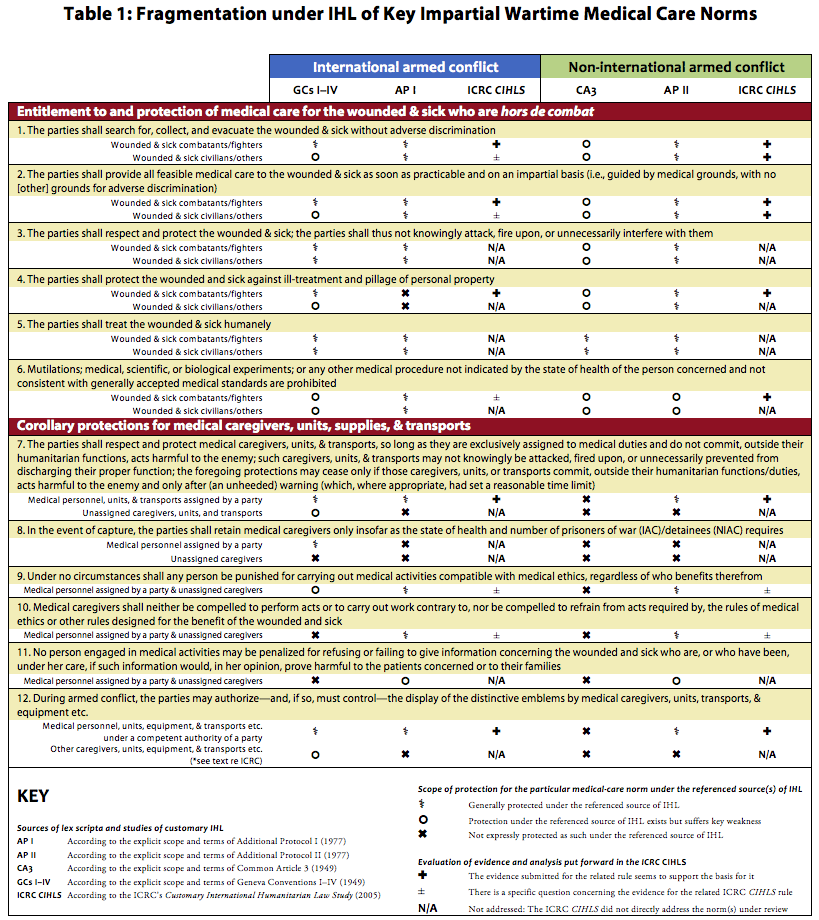

Alongside narrative summaries, for each of the IHL protections outlined below, we use a table (Table 1, which is at the end of this section) to summarize the level of fragmentation (if any) in the lex scripta for the relevant norm. In that same table we also include, where relevant, a snapshot of the rule and the analysis in the Customary IHL Study related to the underlying norm.

Entitlement to and Protection of Medical Care for the Wounded and Sick Hors de Combat

Definition of the wounded and sick

First thing first: who, exactly, falls under the IHL protections for the “wounded and sick”?

There is no general definition that applies across all situations of armed conflict under IHL.[2] While AP I defines the “wounded and sick,” that definition is expressly limited to the purposes of that treaty.[3]

Therefore, as with so many other legal categories lacking a general definition, “common sense and good faith”[4] are the best starting points. Accordingly, the main definitional contours for the condition of being “wounded and sick” are relatively uncontroversial: a person who is in need of medical assistance or care and who refrains from any act of hostility.[5]

Yet whether a particular person qualifies for the specific IHL protections for the wounded and sick requires more information and analysis. Depending on the person and the circumstances she finds herself in, it may entail an assessment of her status under IHL; the category of armed conflict (IAC or NIAC); and the relevant source(s) of IHL (treaty and/or customary).

The main fault line here is whether—in addition to wounded, sick, and shipwrecked combatants and prisoners of war in IAC[6]—civilians in IACs and both fighters and civilians in NIACs qualify for some, or all, of the protections for the wounded and sick.

The answer is clearest under AP I and AP II. All civilians and fighters may qualify for those conventions’ respective protections for the wounded and sick.[7]

For its part, GC IV expressly references wounded and sick civilians and extends certain important protections to them.[8] And GC IV provides particular additional protections to, for instance, wounded and sick “protected persons” interned by the enemy and civilians in occupied territory.[9] But compared to those for their wounded and sick combatant and prisoner-of-war counterparts under GCs I-III, in general the medical-care protections for wounded and sick civilians under GC IV are somewhat weak.[10]

Common Article 3—in laying down generally that the “wounded and sick shall be collected and cared for”[11]—is silent on the matter. The ICRC’s Commentary suggests that the “wounded and sick” under this provision includes both military and civilian persons.[12] That conclusion, however, does not necessarily follow from the text of the article itself, which does not expressly set out the provision’s personal scope. This part of the law, in short, seems to be imprecise. (For their part, both of Additional Protocols aim, in part, to ensure medical protections to all wounded and sick persons—military and civilian alike—hence the explicit language in AP I and AP II to that effect.[13]) While recognizing the imprecision in the text, for the sake of our analysis, we nonetheless assume that the “wounded and sick” in Common Article 3 refers both to the parties to the conflict and to civilians.

As with Common Article 3, the relevant rules on the wounded and sick put forward in the ICRC Customary IHL Study do not expressly include or exclude civilians.[14] The accompanying commentary to the rule, however, has been interpreted to “intimate[] that civilians arguably may be included.”[15] That intimation has been criticized for not citing adequate state practice and sufficiently clear opinio juris on two grounds: first, for purportedly expanding the obligations in GCs I–IV, and, second, for embracing “the admittedly innovative rule” in APs I–II.[16]

Search for, collection, and evacuation without adverse discrimination

Moving on to the actual protections, the starting point is the norm requiring the parties to search for, collect, and evacuate the wounded and sick—and to do so without adverse discrimination. This obligation is subject to practical limitations: military commanders may judge what is possible.[17]

For IACs, this norm is well grounded—especially for wounded, sick, and shipwrecked combatants—in GCs I–II.[18] (Though the temporal scope of obligation varies a bit in the lex scripta.[19]) GC IV leaves a gap in protection: the military parties were obliged only to “facilitate” steps to search for wounded and sick civilians.[20] Civilian, not military, authorities were ultimately responsible for them.[21] For contracting states, AP I closes this gap.[22]

For NIACs, Common Article 3 requires only the “search” element.[23] For contracting states, AP II expressly added the “collection” part but not the “evacuate” component.[24]

Row 1 in Table 1 summarizes the fragmentation in the lex scripta of IHL—and the related analysis in the Customary IHL Study—concerning the norm that the parties shall search for, collect, and evacuate all wounded and sick without adverse discrimination. The argument in the Customary IHL Study that this is a norm applicable in NIAC finds some support in the recent U.S. Department of Defense Law of War Manual.[25] While not expressly recognizing the customary status of the norm, the Manual includes a cognate provision for NIAC—though the Manual maintains the (slight) gap, as a matter of law, in GC IV for wounded and sick civilians in IACs.[26]

All feasible medical care as soon as practicable and on an impartial basis guided by medical grounds

Next is the primary wartime medical-care norm: so long as they refrain from any act of hostility, the wounded and sick hors de combat must receive all feasible medical care and attention required by their condition.[27] That care must be provided as soon as practicable, with the least possible delay, and guided by medical need without adverse discrimination on any other (i.e., non-medical) ground.[28] Willfully leaving the wounded and sick without medical attention and care is prohibited.[29] As is creating conditions that would expose them to contagion or infection.[30]

Imposed on the parties to the conflict, this norm is generally considered an obligation of means.[31] Amid the chaos of war, a party may not be able to provide the requisite medical care through their assigned personnel. In these circumstances, the obligation has been interpreted to include permitting impartial humanitarian organizations to provide that care.[32]

For IACs, GCs I–III, considered in combination, oblige the parties to provide medical care for wounded, sick, and shipwrecked combatants and prisoners of war.[33] GC IV requires medical attention and hospital treatment for “protected persons,” including those interned for security reasons.[34] But it does not expressly impose the obligation with respect to all wounded and sick civilians.[35] AP I flattens this discrepancy by encompassing all wounded and sick civilians (in addition to military wounded and sick).[36]

For NIACs, Common Article 3 requires generally that the “wounded and sick” be cared for.[37] As mentioned above, Common Article 3 thus does not expressly distinguish between fighters and civilians. For its part, AP II clears up any remaining confusion. Under that Protocol, the norm expressly extends to “[a]ll the wounded, sick and shipwrecked, whether or not they have taken part in armed conflict.”[38]

ICL buttresses this IHL obligation. Under certain circumstances, the willful denial of life-saving health care in armed conflict may be interpreted to constitute not only a violation of IHL[39] but also a war crime under ICL.[40] That denial may also—again under certain circumstances—be interpreted under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court to constitute the crime against humanity of murder by omission.[41] Finally, the crime against humanity of extermination, as defined in the Rome Statute, may be committed against members of the civilian population in the event of the deliberate deprivation of access to food and medicine.[42]

Row 2 in Table 1 summarizes the fragmentation in the lex scripta of IHL—and the related analysis in the Customary IHL Study—concerning the norm that the parties shall provide all feasible medical care to the wounded and sick hors de combat as soon as practicable and on an impartial basis. The row indicates two points of fragmentation reflected in the lex scripta. First, GC IV does not impose this norm fully for all civilians. And second, Common Article 3 does not expressly stipulate that such care must be provided impartially. The Customary IHL Study argument that this norm is applicable in NIAC finds support in the recent U.S. Department of Defense Law of War Manual, which includes this norm for NIAC.[43] However, as it did with respect to the search for the wounded, the Manual maintains the (slight) gap in the obligation to care established in GC IV for wounded and sick civilians in IACs (compared to wounded and sick combatants).[44]

Respect and protection of the wounded and sick: prohibition on knowingly attacking, firing upon, or unnecessarily interfering with them

For well over a century, IHL treaties have required the parties not only to care for the wounded and sick but also to respect and protect them.[45] That term of art is not expressly defined in the lex scripta. But, as noted above, the concept has been interpreted to mean, at a minimum, that, so long as they refrain from any hostile acts, the wounded and sick must not knowingly be attacked, fired upon, or unnecessarily interfered with.[46] (This norm does not, however, immunize the wounded and sick—even if they are receiving medical care—from necessary security measures, such as search, capture, or detention.[47])

For IACs, this norm has long-running antecedents. Its modern incarnations are found in GCs I–II, GC IV, and AP I.[48] (GC IV inverses the terminology and amplifies the requirement by providing that wounded and sick civilians “shall be the object of particular protection and respect.”[49]) For NIAC, this norm is not expressly provided in Common Article 3. But it is clearly set down in AP II.[50]

With respect to IACs, these protections are reinforced by the exceptions laid down in IHL treaties that expressly prohibit reprisals against certain wounded and sick.[51] (Prohibitions on similar acts—though not captioned as “reprisals”—have been interpreted by the ICRC to apply to NIACs,[52] even though neither Common Article 3 nor AP II expressly stipulates as much.)

ICL also bolsters this norm. Intentionally directing attacks against buildings where the wounded and sick are collected in IAC and NIAC—so long as those buildings are not military objectives—is penalized as a war crime under the ICC’s jurisdiction.[53]

Row 3 in Table 1 summarizes the fragmentation in the lex scripta of IHL concerning the norm that the parties shall respect and protect the wounded and sick hors de combat, including by not knowingly attacking, firing upon, or unnecessarily interfering with them. (The Customary IHL Study did not directly address this norm by formulating it as a rule.) The row indicates two points of related fragmentation reflected in the lex scripta. Both pertain to Common Article 3, which does not expressly include this norm (i) for fighters or (ii) for civilians.

Protection against ill-treatment and pillage of personal property

The wounded and sick must also be protected against ill-treatment and pillage of their personal property. This norm requires the parties to protect them against the “hyena[s] of the battlefield.”[54] The concept has been interpreted to prescribe a strong affirmative obligation: the parties must take all practicable measures—including, in some cases, using force—to protect the wounded and sick against pillage and ill-treatment by any person (military or civilian) seeking to harm them.[55]

For IACs, this obligation was laid down in GCs I–II and IV.[56] The GC IV provision (concerning civilians), however, imposes a more flexible obligation compared to the counterpart obligations for wounded, sick, and shipwrecked combatants. Under GC IV, the military parties “shall facilitate the steps taken” to protect the civilian wounded and sick against pillage and ill-treatment.[57] AP I does not expressly incorporate this norm.

For NIACs, Common Article 3 says nothing about pillage. But it does prohibit various forms of ill-treatment—though not in that exact terminology—against persons taking no active part in hostilities, including those placed hors de combat by sickness or wounds.[58] AP II expressly includes the two elements of this norm for both military and civilian wounded and sick.[59]

Row 4 of Table 1 summarizes the fragmentation in the lex scripta of IHL—and the related analysis in the Customary IHL Study—concerning the norm that the parties shall protect the wounded and sick against ill-treatment and pillage of personal property. The row indicates five areas of fragmentation in the lex scripta: the less extensive obligation concerning civilians in GC IV; the lack of express protections against pillage in Common Article 3 (for civilians and for fighters) and in AP I; and the lack of express protections against ill-treatment in AP I. The Customary IHL Study does not directly address whether wounded and sick civilians fell under the related proposed norm of customary IHL.[60]

Humane treatment

IHL stipulates that the parties to an armed conflict shall treat the wounded and sick humanely. Broadly formulated on purpose, humane treatment is an “overarching concept.”[61] It is said to assume “its full significance” when “human values appear to be in greatest danger”—such as when persons are prisoned or interned in armed conflict.[62] The modern incarnations of the norm are found in GCs I–IV, Common Article 3, and both Additional Protocols.[63]

Row 5 of Table 1 summarizes the lack of fragmentation in the lex scripta of IHL concerning the norm that the parties shall treat the wounded and sick hors de combat humanely. (The Customary IHL Study does not directly address this particular norm with respect to the wounded and sick as such, though it does put forward a more general norm of humane treatment for all persons hors de combat.[64])

Prohibition on mutilations, certain experiments, and certain other medical procedures

Parties to armed conflict are prohibited from mutilating and engaging in certain experiments and certain other medical procedures against the wounded and sick.[65] The specific scope of obligations may differ significantly depending on the applicable treaty. For its part, ICL fortifies these IHL prohibitions.[66]

Row 6 of Table 1 summarizes the significant fragmentation in the lex scripta of IHL—and the related analysis in the Customary IHL Study—concerning the norm prohibiting mutilations, certain experiments, and certain other medical procedures not indicated by the state of health of the person and not consistent with generally accepted medical standards. Seven elements of fragmentation in the lex scripta emerge. First, GCs I–II prohibit biological experiments but not certain medical and scientific experiments.[67] Second, the reverse is true for GC III (for prisoners of war) and GC IV (for civilians): those treaties prohibit the latter but not the former.[68] Third, none of GCs I–IV contains the more general prohibition against certain other medical procedures that are not indicated by the state of health of the person concerned and that are not consistent with generally accepted medical standards.[69] Fourth and fifth, Common Article 3, while prohibiting mutilations, does not contain any of the more specific prohibitions—whether committed against fighters or against civilians. Sixth and seventh, AP II lays down the more general prohibition against any person in detention, but it does not include the more specific prohibition—against fighters or against civilians—on certain medical, scientific, and biological experiments.[70] These variances in the lex scripta may be interpreted to undermine the overall coherence of the treaty sources for the corresponding general rule put forward in the Customary IHL Study.[71]

Corollary Protections for Medical Caregivers, Transports, Units, and Supplies

Those providing medical care and the means to do so are not specifically protected in themselves but rather as a corollary to the protections for the wounded and sick.

Definition of caregivers, transports, and units

Before going into the protections for them, we must first define who and what are encompassed in these corollary protections.

The starting point is that not all medical caregivers in armed conflict qualify for the protections of medical personnel.[72] Distilled to their core, two general criteria must be met to obtain that status. First, the personnel must be authorized and recognized by (and thus function under the control of) a party to the conflict. Second, they must exclusively be so assigned to—and do in fact—perform medical functions. In general, the same logic holds for medical units[73] (whether mobile or fixed) and medical transports. (Something of an exception is found in GC IV. Pursuant to that treaty, as noted above, in IACs hospitals, their personnel, and their convoys—even though they are not under a party to the conflict’s direct control—may obtain a special status akin to that provided to their military counterparts.[74]) Temporary medical personnel, units, and transports obtain this special status only for the duration of their assignment.[75]

The reason for these requirements is that the protective regime pivots in part on trust and mutual self-interest between the parties. The parties reposed in one another not only the capacity but also the legal duty to oversee and control their respective medical personnel, units, and transports. The obligation on the parties in IACs to subject certain medical personnel to military laws and regulations are examples of that control.[76]

For IACs, under GC I, state armed forces may assign medical personnel from the military medical service, national Red Cross societies, organizations from neutral states, and other organizations.[77] Under GC IV, personnel of civilian hospitals may have a similar status,[78] and in occupied territory medical personnel of all categories shall be allowed to carry out their duties.[79] Without modifying the position of such civilian hospital personnel and medical personnel in occupied territory under GC IV, AP I defines and establishes protections for (other) civilian medical personnel[80] and for civil defense medical service personnel.[81] AP I stipulates that to obtain either of those latter statuses, however, those personnel must be authorized and recognized by a party to the conflict (unlike the civilian hospital personnel under GC IV).[82]

For NIACs, Common Article 3 is silent on medical personnel, units, and transports. They thus do not benefit from any special status under that provision. AP II, however, expressly contemplates those personnel, units, and transports.[83] AP II’s drafting history[84] and the ICRC Commentary[85] seem to establish that, under that Protocol, both the state and the OAG opposing it may assign those personnel, units, and transports. A terrorist designation does not remove that assignment authority established under IHL.

Members of the civilian population as well as independent humanitarian organizations who have not been assigned by a party to the conflict may still provide medical care and attention to the wounded and sick. Numerous IHL treaties—stretching back to GC 1864—expressly recognize their capacity to do so.[86] These unassigned caregivers do not, however, qualify as medical personnel (as they are not under the control of a party). Thus unassigned caregivers do not enjoy the full protections deriving from that special status.

Caregivers not meeting an IHL definition of medical personnel are nonetheless protected as civilians (so long as they do not forfeit that status by, for example, directly participating in hostilities).[87] Moreover, as highlighted below, a number of key IHL protections are intentionally extended to anyone—irrespective of medical-personnel status or not—who provide care to the wounded and sick hors de combat.

Respect and protection of medical personnel, units, and transports: prohibition on knowingly attacking, firing upon, or unnecessarily preventing them from discharging their proper functions

As noted above, the obligations entailed in the duty to respect and protect medical personnel, units, and transports are not expressly enumerated in the lex scripta.[88] But those obligations have been interpreted to mean that, at a minimum, medical personnel, units, and transports—in both IACs and NIACs—must not knowingly be attacked, fired upon, or unnecessarily prevented from discharging their proper functions.[89] In general, those protections may not cease unless medical personnel commit or medical units and transports are being used to commit—outside their humanitarian duties or functions—acts harmful to the enemy.[90] Even then, that protection of medical units and transports may not cease until a warning has been given, setting, wherever appropriate, a reasonable time limit, and after that warning has gone unheeded.[91] (This norm does not immunize those personnel, units, and transports, however, from legitimate security measures such as search.[92])

What about unassigned medical caregivers, units, and transports? Under GC IV, in IACs the above-mentioned respect-and-protect obligations also extend to the following caregivers and objects:

- “Civilian hospitals organized to give care to the wounded and sick, the infirm and maternity cases;”[93]

- “Persons regularly and solely engaged in the operation and administration of civilian hospitals […]”[94] as well as “[o]ther personnel who are engaged in the operation and administration of civilian hospitals […], while they are employed on such duties;”[95] and

- “Convoys of vehicles or hospital trains on land or specially provided vessels on sea, conveying wounded and sick civilians, the infirm and maternity cases […].”[96]

Other unassigned medical caregivers, units, and transports—whether in IACs or NIACs—do not benefit under IHL from the so-called “special protections” for medical personnel, units, and transports assigned by a party to the conflict. Rather, such unassigned caregivers are generally protected under IHL as civilians, so long as they do not take a direct part in hostilities.[97] And such unassigned units and transports are general protected under IHL as civilian objects (so long as they are not military objectives).

With respect to IACs, the above-mentioned protections against attack are reinforced by the exceptions laid down in IHL treaties expressly prohibiting reprisals against certain medical personnel and objects.[98] (As mentioned above, prohibitions on similar acts—though not captioned as “reprisals”—have been interpreted by the ICRC to apply to NIACs,[99] even though neither Common Article 3 nor AP II expressly stipulates as much.)

Row 7 of Table 1 summarizes the fragmentation in the lex scripta of IHL—and the related analysis in the Customary IHL Study—concerning the norm that the parties shall respect and protect medical personnel, units, and transports. Five areas of fragmentation in the lex scripta emerge. First, in IACs not all unassigned caregivers, units, and transports under GC IV and AP I are specially protected—only those civilian hospitals, their personnel, and their convoys that are expressly protected under GC IV are.[100] Second, AP II does not include any such special protections for unassigned medical caregivers, units, and transports. Third and fourth, Common Article 3 contains no cognate norm for assigned personnel, units, and transports, nor for their unassigned counterparts. The related norm put forward in the Customary IHL Study encompasses only medical personnel, units, and transports assigned by a party to the conflict.[101] It thus excludes from its scope those who are unassigned.

Capture, detention, and retention

With few limited exceptions, IHL does not protect medical personnel against capture or detention.[102] Those exceptions are laid down in GC I. That treaty contemplates that medical personnel (except those from neutral states[103]) may fall into the hands of the enemy party.[104] In principle, certain such personnel—in particular, military medical service members as well as authorized and recognized Red Cross societies and those from other voluntary relief societies[105]—may not be detained. Rather, they may retained, but only insofar as the state of health and number of prisoners of war require.[106]

In comparison, IHL treaty provisions governing NIAC do not directly protect medical personnel from being captured, detained, or retained.[107] As a result, the state armed forces are not obliged to afford retained status to any captured medical personnel of an organized armed group.[108] (Nor in NIACs are OAGs obliged to afford the medical personnel of the state armed forces, upon capture, retained status.)

Row 8 of Table 1 summarizes the fragmentation in the lex scripta of IHL concerning the norm that medical caregivers shall, upon capture, not be detained but rather only retained, and only then insofar as the state of health and number of prisoners of war or other detainees, as relevant, require. Seven elements of fragmentation in the lex scripta emerge. In short, in IACs certain assigned medical personnel—namely, permanent military medical personnel and authorized medical personnel of aid societies—benefit from such retained status.[109] No IHL treaty establishes the status of retained personnel for any assigned medical personnel in NIACs. Nor does any IHL treaty establish that status for any unassigned caregiver in IACs or in NIACs. (The Customary IHL Study did not directly address this norm.)

Prohibition on punishment

The threat of punishment may act as a strong deterrent to giving medical care to the enemy. Developed out of the abuses against those who provided care to the enemy during WWII, GC I lays down a prohibition on convicting anyone for having nursed the wounded or sick.[110] This prohibition extends not only to the medical personnel assigned by a party to the conflict but to anyone who provided such care.[111] (However, if a wounded terrorist is considered a civilian, rather than a combatant, these protections in GC I may not necessarily apply with respect to that person.)

Over time, states strengthened this norm. Both AP I and AP II provide that “[u]nder no circumstances shall any person be punished for carrying out medical activities compatible with medical ethics, regardless of the person benefiting therefrom.”[112] Common Article 3, however, does not expressly prohibit punishment of medical activities.

Row 9 of Table 1 summarizes the fragmentation in the lex scripta of IHL[113]—and the related analysis in the Customary IHL Study—concerning the norm that under no circumstances shall any person be punished for carrying out medical activities compatible with medical ethics, regardless of who benefits therefrom. Mirroring the intent of the drafters of GC I, AP I, and AP II, we make no distinction for this norm between assigned and unassigned caregivers. Two elements of fragmentation in the lex scripta still emerge. First, the cognate norm in GC I, while revolutionary, expressly prohibits only convicting and molesting (in the sense of ill-treating) persons who nursed the wounded and sick. (AP I and AP II prohibit all forms of punishment more broadly and expand the scope of protection to encompass all medical activities compatible with medical ethics.) And second, Common Article 3 contains no protections whatsoever against punishment of medical caregivers. The related norm put forward in the Customary IHL Study was based largely in the formulations set down in AP I and AP II. Yet the authors cited military manuals and national legislation only from states that are party to one or both of those Protocols.[114] (The prohibition on punishing medical activities in NIACs, in particular, was noticeably absent from the recent U.S. Department of Defense Law of War Manual.[115])

Prohibition on illegitimate compulsion

Amid the tumult of war, caregivers often face increased pressure to act against their patients’ medical interests. That pressure may peak when the patient is designated an enemy of the state, such as a terrorist.

An implicit prohibition on illegitimate compulsion of caregivers can be read into various IHL protections. Consider the provisions prescribing humane treatment, those requiring that care be provided impartially, and those prohibiting certain medical experiments. [116]

Yet states did not agree to explicit IHL protections against compelling illegitimate acts or omissions of caregivers until the Additional Protocols. Generally stated, under both AP I and II, anyone who engages in medical activities—not just medical personnel—is protected against being compelled to act contrary to medical ethics and other rules designed to protect the wounded and sick.[117] Those persons are also protected against being compelled to refrain from acting in accordance with those ethics and rules.[118] These norms help protect against unnecessary procedures. But they also prohibit tasks that are incompatible with the humanitarian mission, such as camouflaging military operations under the cover of medical functions.[119]

ICL fortifies these protections by imposing individual criminal liability for various so-called “medical war crimes.”[120] IHRL, too, may help safeguard the underlying protection, including by establishing normative points of reference concerning medical ethics.[121]

Row 10 of Table 1 summarizes the fragmentation in the lex scripta of IHL—and the related analysis in the Customary IHL Study—concerning the norm that medical caregivers shall neither be compelled to perform acts or to carry out work contrary to, nor be compelled to refrain from acts required by, the rules of medical ethics or other rules designed for the benefit of the wounded and sick. In line with the drafters of AP I and AP II, we make no distinction for this norm between authorized personnel and unassigned caregivers. Two elements of fragmentation in the lex scripta still emerge. Both flow from the lack of express protections against such compulsion in GCs I–IV and in Common Article 3. Meanwhile, the related norm put forward in the Customary IHL Study derives significantly from the Additional Protocols.[122] Yet all of the relevant cited military manuals and national legislation were from parties to AP I and/or AP II.[123]

Limitations on denunciation

Under IHL, may a caregiver be compelled to give authorities information on persons whom they have treated? Not only health-related information, but information on their patients’ activities, connections, and position—or even on the existence of the wounded?[124]

As noted earlier, concern regarding such wartime denunciation arose after WWII.[125] During that conflict, occupying forces had “ordered inhabitants, including doctors, to denounce [to the authorities] the presence of any presumed enemy, under threat of grave punishment.”[126] Of course, if they were to be denounced to the authorities, the wounded were less likely to seek treatment. While drafting GCs I–IV, the delegates did not agree, however, on whether to establish a protection allowing medical personnel and the civilian population to conceal information about the wounded whom they had cared for.[127]

After wide-ranging and often heated discussions during the Diplomatic Conference, non-denunciation regulations were laid down in the Additional Protocols.[128] The relevant rules in AP I and AP II are fashioned slightly differently.[129] But the upshot is that the protection against compulsory denunciation[130] in both treaties may be subject to certain national law.[131] Conditioning the international legal norm on various domestic legislations weakened these protections.[132]

Row 11 of Table 1 summarizes the fragmentation in the lex scripta of IHL[133] concerning the norm that no person engaged in medical activities may be penalized for refusing or failing to give information concerning the wounded or sick who are, or have been, under her care, if such information would, in her opinion, prove harmful to the patients concerned or to their families. Four elements of fragmentation in the lex scripta emerge. First, GCs I–IV contain no such protection. Second, neither does Common Article 3. Third and fourth, both AP I and AP II subject the norm to certain domestic legislation. (The Customary IHL Study does not put forward a rule that expressly encompassed that norm. Though, in the discussion of a related rule, the authors comment on respect for medical secrecy more broadly.[134])

Display of the distinctive emblems

The use of protected emblems has long been a key element of IHL.[135] They are intended to signify one thing “of immense importance: respect for the individual who suffers and is defenceless, who must be aided, whether friend or enemy, without distinction of nationality, race, religion, class or opinion.”[136] Today, the distinctive emblems include the red cross, red crescent, red lion and sun, and red crystal.[137]

In general, with few exceptions, IHL provides that the distinctive emblems may be used only under the control of the competent authority of a party to the conflict.[138] That is because the protective regime pivots in part on the trust between the parties, who must ensure that the “special” status of medical personnel, units, and transports is not abused. Thus, as with the assignment of medical personnel, a key criterion of authorizing the use of the distinctive emblem is that the entity is subject to the party’s control.[139] (The ICRC and certain other parts of the International Movement of the Red Cross and Red Crescent are exceptions, though GC I contemplated that National Red Cross Societies may work under a party’s control.[140])

The authorization of the use of the distinctive emblems—for protective purposes for medical personnel, units, transports, equipment, and supplies—is extensively regulated in GCs I–II, GC IV, and AP I.[141] Common Article 3, however, contains no provisions on the emblems. A major development for NIAC occurred in AP II. That Protocol reposes the power to authorize the emblems not only in states but also in organized armed groups.[142] A terrorist designation does not modify that OAG’s power to do so under IHL.

ICL buttresses this system of control. The ICC Statute penalizes as a war crime in IAC making improper use of the emblems where such use results in death or serious personal injury.[143] It also lays down as a war crime in both IAC and NIAC intentionally directing attacks against medical personnel and objects displaying the distinctive emblems in conformity with IHL.[144]

Row 12 of Table 1 summarizes the fragmentation in the lex scripta of IHL, and the related analysis in the Customary IHL Study, concerning the norm that the parties may authorize—and, if they do so, must control—the display of the distinctive emblems by medical caregivers, units, transports, equipment, and certain other things used to discharge their proper functions.[145] Five elements of fragmentation emerge in the lex scripta. One of those elements relates to the fact that under GC IV only some unassigned caregivers and objects—namely, authorized civilian hospitals, their personnel, and their convoys[146]—may use the emblem. Three more of those fragmentation elements come from the lack of authorization in AP I, in Common Article 3, or in AP II for any unassigned caregivers, units, and transports to display the emblems. And the fifth fragmentation element flows from the lack of provisions in Common Article 3 concerning the authorization of the emblems by any personnel or objects controlled by the parties. The rule put forward in the Customary IHL Study addresses the use of the emblems by medical personnel, units, and transports assigned by a party to the conflict, not their unassigned counterparts.[147] For NIAC, the main source of lex scripta for this norm is found in AP II.[148]

Footnotes

[1] For those interested in the technical scope of the broader lex scripta, the accompanying Compendium provides verbatim excerpts of the medical-care protections in GCs I–IV, Common Article 3, and the Additional Protocols.

[2] AP I contains a definition of the wounded and sick expressly for purposes of that Protocol. For the purposes of AP I, “wounded” and “sick” are defined as meaning “persons, whether military or civilian, who, because of trauma, disease or other physical or mental disorder or disability, are in need of medical assistance or care and who refrain from any act of hostility.” Article 8(a) AP I [italics added]. The term “wounded and sick” “also cover[s] maternity cases, new-born babies and other persons who may be in need of immediate medical assistance or care, such as the infirm or expectant mothers, and who refrain from any act of hostility.” Id. See also article 8(b) AP I.

[3] Article 8 chapeau and (a) AP I.

[4] ICRC, Commentary on GC IV, p. 134.

[5] See, e.g., Article 8(a) AP I; see also ICRC, Commentary on the APs, para. 4638.

[6] Recall that GC I extensively elaborates obligations concerning wounded and sick members of the armed forces in the field. GC II extends the protective regime to wounded, sick, and shipwrecked members of the armed forces at sea. See, e.g., Jann K. Kleffner, “Protection of the Wounded, Sick, and Shipwrecked,” in The Handbook of International Humanitarian Law 322 (3d ed., ed. Fleck, 2014). GC III regulates the status and treatment of prisoners of war. In particular, GC I applies with respect to wounded and sick—while GC II applies with respect to wounded, sick, and shipwrecked—persons who are entitled to prisoner-of-war status in accordance with article 4(A) GC III. Article 13 GC I and GC II. According to article 13 GC I, the Convention shall apply with respect to the wounded and sick belonging to one of six listed categories; see also articles 13 GC II and 44(8) AP I. Those categories include (but are not limited to) members of the armed forces of a party to the conflict; members of militia or volunteer corps forming part of those armed forces; and members of other militaries or volunteer corps belonging to a party to the conflict so long as they fulfill certain conditions. For the full list: article 13(1)–(6) GC I and GC II; see also article 4(A) GC III. Moreover, the “wounded and sick of a belligerent who fall into enemy hands shall be prisoners of war, and the provisions of international law concerning prisoners of war shall apply to them.” Article 14 GC I; this article is subject to article 12 GC I; see also article 16 GC II.

[7] Article 8(a) AP I and 7(1) AP II. Part III (articles 7–12) of AP II relates to the wounded, sick, and shipwrecked. Unlike AP I, AP II does not contain definitions of the terms “wounded and sick,” though there appears to be general agreement among commentators that these terms have the same meaning in AP II as in AP I. Thus in AP II “wounded and sick” would seem to encompass at least those “persons, whether military or civilian, who, because of trauma, disease or other physical or mental disorder or disability, are in need of medical assistance or care and who refrain from any act of hostility.” This view is supported by the explicit text of article 7(2) AP II (“[a]ll the wounded, sick and shipwrecked, whether or not they have taken part in the armed conflict, […].”) [italics added]. Moreover, in its Commentary, the ICRC emphasizes that “[t]he definition of wounded and sick protected by this Part is based on two criteria: 1) requiring medical care; [and] 2) refraining from any act of hostilities.” See, e.g., ICRC, Commentary on the APs, paras. 4636–4639.

[8] E.g., article 16 GC IV.

[9] E.g., articles 38(2), 55(1), 81(1)–(2), 91–92, 109(1), and 127(2)–(3) GC IV.

[10] E.g., compare article 16(1)–(2) GC IV with article 12(1) GC I; see also ICRC, Commentary on GC IV, p. 135 (stating that “saving civilians is the responsibility of the civilian authorities rather than of the military.”).

[11] Common Article 3(2) GCs I–IV.

[12] ICRC, Commentary on GC IV, pp. 40–41. In support of this view, Amrei Müller, “States’ obligations to mitigate the direct and indirect health consequences of non-international armed conflicts: complementarity of IHL and the right to health,” 95 IRRC No. 889 (2013) 136 (arguing thus that “treaty rules on the wounded and sick were more inclusive in [NIAC] than in [IAC] already in 1949, when Common Article 3 of GC I–IV was adopted.”) [citations omitted].

[13] See, e.g., ICRC, Commentary on the APs, para. 4624; Michael Bothe, Karl Josef Partsch, and Waldemar A. Solf, New Rules for Victims of Armed Conflicts: Commentary on the Two 1977 Protocols Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 116 (2d. ed., 2013) (commenting, with respect to the personal scope of article 10 AP I, as read in conjunction with article 8(a) AP I, that “Article 10 parallels Art. 12 of the First and Second Conventions. Although Art. 10 applies to all wounded, sick, and shipwrecked, be they military or civilian, it does not really add anything essential to the Conventions as far as military persons are concerned. Its main importance lies in that it ensures the protection and care of wounded, sick and shipwrecked civilians.”) [italics original].

[14] ICRC, CIHLS, Vol. I: Rules, Rules 109–111, pp. 396, 400, 403.

[15] James P. Benoit, “Mistreatment of the Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked by the ICRC Study on Customary International Humanitarian Law,” 11 YIHL (2008) 207 [hereinafter, Benoit, “Mistreatment of the Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked”]; ICRC, CIHLS, Vol. I: Rules, Rules 109, p. 399 (stating, with respect to the scope of application, that rule 110 “applies to the wounded, sick and shipwrecked regardless to which party they belong, but also regardless of whether or not they have taken a direct part in hostilities.”).

[16] Benoit, “Mistreatment of the Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked,” supra note 15, at pp. 207–208.

[17] See, e.g., U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual §§ 7.4.4, 13.7.2, and 17.4.3 (2015).

[18] Articles 15(1) GC I and 18(1) GC II.

[19] Compare article 15(1) GC I with article 18(1) GC II.

[20] Article 16(2) GC IV.

[21] See ICRC, Commentary on GC IV, p. 135.

[22] Article 10 AP I.

[23] Common Article 3(2) GCs I–IV.

[24] Article 8 AP II; see, e.g., ICRC, Commentary on the APs, para. 4649. See also International Institute of Humanitarian Law, The Manual on the Law of Non-International Armed Conflict with Commentary paras. 3.1.b and 3.1.4 (2006).

[25] U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual § 17.14.3 (2015).

[26] Id. at § 7.16.1.

[27] See, e.g., ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rule 110, pp. 400–403.

[28] Id. See also International Institute of Humanitarian Law, The Manual on the Law of Non-International Armed Conflict with Commentary paras. 3.1.c and 3.1.4 (2006).

[29] Articles 12 GC I and 12 GC II. See also U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual §§ 7.5 and 7.5.2.1 (2015).

[30] See, e.g., U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual §§ 7.5 and 7.5.2.1 (2015).

[31] ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rule 110, p. 402.

[32] Alexander Breitegger, “The legal framework applicable to insecurity and violence affecting the delivery of health care in armed conflicts and other emergencies,” 95 IRRC No. 889 (2013) 92 [citations omitted] [hereinafter Breitegger, “The legal framework”].

[33] Articles 12(2) and 15(1) GC I, 12(2) and 18(1) GC II, and 15 GC III.

[34] E.g., article 81(1) GC IV.

[35] Compare article 16 GC IV with articles 12(2) and 15(1) GC I, 12(2) and 18(1) GC II, and 15 GC III.

[36] Article 8(a) AP I.

[37] Common Article 3(2) GCs I–IV.

[38] Article 7 AP II. AP II also expressly requires medical treatment for those whose liberty has been restricted in relation to the armed conflict. Article 5(1)(a) AP II.

[39] Including, in international armed conflict, a grave breach. Articles 50 GC I, 51 GC II, 130 GC III, 147 GC IV, and 85(2) AP I.

[40] When committed, for instance, in relation to an IAC against a protected person by the adverse party. Articles 11(4) AP I; 8(2)(a)(i) and (iii) ICC RS. Pursuant to the chapeau in article 8(1) ICC RS, “[t]he Court shall have jurisdiction in respect of war crimes in particular when committed as part of a plan or policy or as part of a large-scale commission of such crimes.”

[41] See article 7(1)(a) ICC RS. The relevant chapeau elements under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court would need to be met. Pursuant to article 7(1) ICC RS, for the list of penalized acts to constitute a crime against humanity, they must be “committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack,” and pursuant to article 7(2)(a) ICC RS, an “attack directed against any civilian population” is defined as “a course of conduct involving the multiple commission of acts referred to in [article 7(1) ICC RS] against any civilian population, pursuant to or in furtherance of a State or organizational policy to commit such attack.” See, e.g., Breitegger, “The legal framework,” supra note 32, at p. 107 [citations omitted].

[42] Article 7(1)(b) and (2)(b) of the Elements of Crimes of the ICC RS. See also Breitegger, “The legal framework,” supra note 32, at p. 107 [citations omitted].

[43] U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual § 17.14.2 (2015).

[44] Compare id. at § 7.5.2 with id. at §§ 7.16 and 7.16.1.

[45] See the discussion and corresponding citations supra Section 3: “IHL Treaties — Antecedents to the Geneva Conventions of 1949.”

[46] E.g., U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual §§ 7.3.3 and 17.14.1.2 (2015). See also International Institute of Humanitarian Law, The Manual on the Law of Non-International Armed Conflict with Commentary para. 3.1.a (2006).

[47] E.g., U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual §§ 7.3.3.2–3 and 17.14.1.2 (2015).

[48] Articles 12(1) GC I, 12(1) GC II, 16(1) GC IV, and 10(1) AP I.

[49] Article 16(1) GC IV.

[50] Article 7(1) AP II.

[51] E.g., articles 46 GC I, 47 GC III, 13(3) GC III, and 33(3) GC IV.

[52] ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rule 148, pp. 526–29; but see, e.g., Dinstein, Non-International Armed Conflicts in International Law 140–142 (2014) [hereinafter, Dinstein, NIACs in International Law].

[53] Articles 8(2)(b)(ix) and (2)(e)(iv) ICC RS.

[54] ICRC, Commentary on GC I, p. 152.

[55] E.g., U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual § 7.4.2 (2015) (citing to ICRC, Commentary on GC I, p. 152).

[56] Articles 15(1) GC I, 18(1) GC II, and 16(2) GC IV.

[57] Article 16(2) GC IV.

[58] Common Article 3(1) GCs I–IV.

[59] Article 8 AP II. See also International Institute of Humanitarian Law, The Manual on the Law of Non-International Armed Conflict with Commentary para. 3.1.b (2006).

[60] ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rule 111, pp. 403–406.

[61] Id. at Rule 87, pp. 306–307

[62] ICRC, Commentary on GC IV, p. 205.

[63] Articles 3(1) and 12(2) GC I, 3(1) and 12(2) GC II, 3(1) and 13(1) GC III, 3(1), 27(1), and 37(1) GC IV, 10(1) and 75(1) AP I, 4(1), 5(3), and 7(2) AP II. See also International Institute of Humanitarian Law, The Manual on the Law of Non-International Armed Conflict with Commentary para. 3.1.c (2006).

[64] ICRC, CIHLS, Rules: Part I, Rule 87, pp. 306–308.

[65] Articles 3(1)(a), 12(2), and 50 GC I, 3(1)(a), 12(2), and 51 GC II, 3(1)(a), 13(1), and 130 GC III, 3(1)(a), 32, and 147 GC IV, 11 and 75(2)(4) AP I, 4(2)(a) and 5(2)(e) AP II. See also International Institute of Humanitarian Law, The Manual on the Law of Non-International Armed Conflict with Commentary para. 1.2.4.9 (2006).

[66] See, e.g., ICRC, CIHLS, Rules: Part I, Rule 92, pp. 322–323.

[67] Articles 12(2) GC I and 12(2) GC II.

[68] Articles 13(1) GC III and 32 GC IV; but see article 147 GC IV (which includes “biological experiments” as one of the acts that may constitute a grave breach where committed against a person protected by the Convention).

[69] Compare articles 12(2) GC I, 12(2) GC II, 13(1) GC III, and 32 GC IV with articles 11(1) AP I and 5(2)(e) AP II.

[70] Compare article 5(2)(e) AP II with articles 12(1) GC I, 12(1) GC II, 13(3) GC III, 32 GC IV, and 11(2)(b) AP I.

[71] ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rule 92, pp. 320–23.

[72] Kalshoven, for example, breaks down the relevant legal categories of aid workers as follows: (i) personnel attached to “medical units,” including (i)(a) military medical units and their personnel and (i)(b) civilian medical units and their staff; (ii) other professional medical aid workers; and (iii) persons who are incidentally involved with the card of the wounded or sick. Frits Kalshoven, “Legal Aspects of ‘Medical Neutrality,’” in Reflections on the Law of War 1027–1031 (2007). See also International Institute of Humanitarian Law, The Manual on the Law of Non-International Armed Conflict with Commentary para. 3.2.2 (2006); Michael N. Schmitt, “Targeting in Operational Law,” in The Handbook of the International Law of Military Operations 263 (eds. Terry D. Gill and Dieter Fleck, 2010) (“Individuals who are not assigned to medical […] duties are not protected by the rule even if acting in that capacity.”). Kalshoven gives the following examples of those not eligible for special protection: “the general practitioner and the chemist, health care institutions not recognised or authorised by the qualified authorities, as well as the staff of a non-recognised society for medical aid working in an area of conflict outside their own country.” Frits Kalshoven, “Legal Aspects of ‘Medical Neutrality,’” in Reflections on the Law of War 1030 (2007); see also id. at p. 1031 (summarizing “that the protection of the function that may be widely termed as the care of the wounded and sick victims of conflict situations varies from the minimal (every civilian) to the very extensive (the officially recognised medical formation); and that the requirements for the most extensive protection are strict. Many professional medical aid workers remain denied this protection, including the use of the red cross or red crescent as protective emblem. This applies to the not-recongised local health workers in countries where only highly rudimentary organised health provisions exist as much as to the doctors and other medical aid workers who are dispatched to conflict areas by non-recognised societies. The latter’s problems increase if they enter such an area without official permission.”).

[73] See, e.g., articles 8(e) and 12(2) AP I; ICRC, Commentary on the APs, paras. 522–28; ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rule 28, p. 95 (“While a lot of practice does not expressly require medical units to be recognised and authorised by one of the parties, some of it refers to the provisions of Additional Protocol I, or does require such authorisation in another way. Unauthorised medical units must therefore be regarded as being protected according to the rules on the protection of civilian objects […], but do not have the right to display the distinctive emblems.”) [footnotes omitted; italics added].

[74] Articles 18(1), 19, 20, and 21 GC IV.

[75] See Article 8(k) AP I; see also, e.g., ICRC, Commentary on the APs, paras. 390–96.

[76] E.g., article 26(1) GC I.

[77] Articles 24, 26, and 27 GC I.

[78] Article 20 GC I.

[79] Article 56(1) GC IV; see also ICRC, Commentary on GC IV, p. 314.

[80] Articles 8(c) and 15 AP I.

[81] Article 61(a)(vi) and (c) AP I.

[82] On civilian medical personnel, see ICRC, Commentary on the APs, paras. 349 and 610; on medical personnel (including members of the armed forces and military units assigned to civil defense organizations) and matériel of civil defense organizations, articles 61(a)(iv) and (c), 62, and 67 AP I. See Michael N. Schmitt, “Targeting in Operational Law,” in The Handbook of the International Law of Military Operations 263 (eds. Terry D. Gill and Dieter Fleck, 2010).

[83] Article 9 AP II.

[84] A number of statements given by delegates during the Diplomatic Conference that led to AP II confirm the plausibility of the interpretation that the drafters of the protocol did indeed intend for the dissident armed forces or other organized armed groups (so long as those forces or groups meets the article 1(1) AP II threshold) to be capable, alongside the concerned state, of recognizing and authorizing medical personnel for purposes of AP II. For example, a member of the U.S. delegation stated that “the word ‘recognized’ used in that context [of a definition of “medical personnel” in an earlier draft of AP II] meant that the organization in question had been recognized as an aid society by the competent authorities, namely, the Government in the case of an international armed conflict or a party to the conflict in the case of a non-international armed conflict […].” O.R. Vol. XII, CDDH/II/SR.80, p. 270, para. 21 [italics added]. (Note the use by the delegate of the indefinite article “a”—rather than the definite article “the”—preceding “party,” which can be read to imply that the delegate was submitting that either the government or the other party to the armed conflict—namely, the dissident armed forces or organized armed group meeting the article 1(1) AP II criteria—could recognize and authorize medical personnel.) Along the same lines, a delegate of the U.S. stated that “the word ‘authorized’ meant that the organization had been specifically authorized by a party to the conflict to form medical units in order to care for the wounded and the sick.” Id. [italics added]. A delegate of Australia “fully supported that view.” Id. at. p. 271, para. 22. Also seeming to promote that view, more recently, in 2004, the United Kingdom Manual of the Law of Armed Conflict states that with respect to AP II “[i]n the case of insurgents, [the competent authority] will be the de facto authority.” United Kingdom Ministry of Defence, Joint Service Publication 383, The Joint Service Manual of the Law of Armed Conflict para. 15.48 fn 113 (2004). Note that the Rapporteur of the Drafting Committee, when discussing the work of the small group that had discussed part of an earlier draft definition of “medical personnel” for use in AP II, stated that “[i]t had been considered necessary to specify that aid societies other than Red Cross organizations must be located within the territory of the State where the armed conflict is taking place,” as the drafters sought “‘to avoid the situation of an obscure private group from outside the country establishing itself as an aid society within the territory and being recognized by the rebels.” O.R. Vol. XII, CDDH/II/SR.80, p. 270, para. 15 (Mr. Bothe, Federal Republic of Germany); see also article 18(1) AP II.

[85] E.g., ICRC, Commentary on the APs, p. 1420, para. 4660–6; see also O.R. Vol. XIII, CDDH/235/Rev.1, pp. 303–305.

[86] See infra Section 4: “Corollary Protections for Medical Caregivers, Transports, Units, and Supplies.”

[87] See, e.g., ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rule 25, p. 82 (explaining that “[o]nly medical personnel assigned to medical duties by a party to the conflict enjoy protected status. Other persons performing medical duties enjoy protection against attack as civilians, as long as they do not take a direct part in hostilities (see Rule 6 [CIHLS]). Such persons are not medical personnel and as a result they have no right to display the distinctive emblems.”) [italics added]; see also Frits Kalshoven, “Legal Aspects of ‘Medical Neutrality,’” in Reflections on the Law of War 1030 (2007) (“The protection ‘as a civilian’ is also suspended if and as long as such persons ‘participate directly in the hostilities’. This concept is not defined further and is subject to diverse interpretations. The possibility cannot be altogether excluded that one party to the conflict assumes that, for instance, the activities of a medical team that appears to be acting without special protection on the side of the opposing party constitutes such direct participation and as a result deliberately attacks the team. Such an interpretation may, in light of better insight, be unacceptable, but the damage will have been done before anyone can persuade the party of the incorrectness of the view.”).

[88] Compare the definitions put forward in, for example, ICRC, Commentary on GC I, pp. 134 and 220 with U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual §§ 7.8.2, 7.10.1, 17.15.1.2, and 17.15.2.2 (2015).

[89] E.g., U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual §§ 7.8.2, 7.10.1, and 17.15.1.2 (2015).

[90] See articles 21 GC I, 34(1) GC II, 19 and 21 GC IV, 13(1) AP I, and 11(2) AP II; the terminology is slightly different in some of the provisions. See also, e.g., ICTY, Prosecutor v. Galić, Appeals Chamber, Judgement No. IT-98-29-A, November 30, 2006, paras. 341–342, 344, and 346; U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual §§ 7.10.3.1, 7.11.1, 7.12.6, 7.17.1, 7.18.1, and 17.15.2 (2015); ICRC, Commentary on the APs, paras. 551 and 4728; ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rules 25, 28, and 29, pp. 79, 84–86, 91, 97–98, and 102. The treaty rules on loss of protection expressly regulate medical units and/or transports; nonetheless, “the rule on loss of protection contained therein can be applied by analogy to medical personnel.” ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rule 25, p. 85; this view is supported, at least with respect to IAC, in U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual § 7.8.3 (2015) (citing to ICRC, Commentary on GC IV, p. 221). Concerning the position of civil defense personnel and objects, see articles 65(1) and 67(e) AP I.

[91] See articles 21 GC I, 34(1) GC II, 19 and 21 GC IV, 13(1) AP I, and 11(2) AP II; again, the terminology is slightly different in some of the provisions. See also, e.g., ICTY, Prosecutor v. Galić, Appeals Chamber, Judgement, No. IT-98-29-A, November 30, 2006, paras. 344 and 346; U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual §§ 7.10.3.2, 7.11.1, 7.12.6.1, 7.17.1.2, 7.18.1, and 17.15.2 (2015). ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rules 25, 28, and 29, pp. 79, 84–86, 91, 97–98, and 102.

[92] See, e.g., U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual §§ 7.8.2.2, 7.10.1.2, 17.15.1.2, and 17.15.2.2 (2015).

[93] Article 20(1) GC IV. Pursuant to article 18(2) GC IV, “States which are Parties to a conflict shall provide all civilian hospitals with certificates showing that they are civilian hospitals and that the buildings which they occupy are not used for any purpose which would deprive these hospitals of protection in accordance with Article 19 [GC IV].”

[94] Articles 19 and 20(1) GC IV.

[95] Article 20(3) GC IV.

[96] Article 21(1) GC IV. Pursuant to article 22(1) GC IV, “[a]ircraft exclusively employed for the removal of wounded and sick civilians, the infirm and maternity cases, or for the transport of medical personnel and equipment, shall not be attacked, but shall be respected while flying at heights, times and on routes specifically agreed upon between all the Parties to the conflict concerned.”

[97] Under IHL, attacks directed at unassigned caregivers—so long as they have not forfeited their protections under the law—would be prohibited based on those persons’ civilian status and on the respect due to the wounded and sick hors de combat. See, e.g., ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rule 25, p. 82 (explaining that “[o]nly medical personnel assigned to medical duties by a party to the conflict enjoy protected status. Other persons performing medical duties enjoy protection against attack as civilians, as long as they do not take a direct part in hostilities (see Rule 6 [CIHLS]).”) [italics added].

[98] E.g., articles 46 GC I, 47 GC III, 13(3) GC III, and 33(3) GC IV.

[99] ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rule 148, pp. 526–29; but see, e.g., Dinstein, NIACs in International Law, supra note 52, at pp. 140–142.

[100] Pursuant to article 1(3) AP I, the Protocol “supplements” GCs I–IV; AP I does not modify, but does incorporate by reference, the scope of application under GC IV concerning the special protections for unassigned caregivers, units, and transports.

[101] ICRC, CIHLS, Part I: Rules, Rules 25, 28, and 29, pp. 81–83, 95, and 100.

[102] E.g., Articles 30(1) and 32(1) GC I and 36 GC II.

[103] Article 32(1) GC I.

[104] Article 30(1) GC I. See ICRC, Commentary on GC I, p. 242 (stating that “[t]he wording [medical personnel ‘who fall into the hands of the adverse Party’] implies that the capture of medical personnel must be a matter of chance and depend upon fluctuations at the battle front; for it is hardly conceivable that a belligerent should deliberately try to capture such personnel. An organized ‘medical hunt’ would certainly be a sorry sight and completely contrary to the spirit of the Geneva Convention.”).

[105] In particular, those defined in articles 24 (military medical service) and 26 (authorized and recognized Red Cross societies and other voluntary relief societies) GC I.

[106] Articles 28(1) GC I and 33 GC III; see also United Kingdom Ministry of Defence, Joint Service Publication 383, The Joint Service Manual of the Law of Armed Conflict paras. 7.8 and 8.58 (2004).

[107] See, e.g., U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual § 17.15.1.2 (2015) (stating with respect to IHL applicable to NIAC that “[t]he respect and protection afforded medical […] personnel do not immunize them from search, or from other necessary security measures, or from capture and detention” and that “AP II and applicable treaties to which the United States is a Party (such as the 1949 Geneva Conventions) do not afford medical […] personnel belonging to non-State armed groups retained personnel status if captured.”) [internal reference omitted].

[108] Id.

[109] Article 28(1) GC I. Pursuant to article 32(1) GC I, the personnel belonging to neutral countries (as laid down in article 27 GC I) “may not be detained”; rather, pursuant to article 32(2) GC I, those personnel shall, unless otherwise agreed, “have permission to return to their country, or if this is not possible, to the territory of the Party to the conflict in whose service they were, as soon as a route for their return is open and military considerations permit.”

[110] Article 18(3) GC I.

[111] ICRC, Commentary on GC I, p. 193.

[112] Articles 16(1) AP I and 10(1) AP II [italics added]; see also article 17(1) AP I (stipulating that “[n]o one shall be harmed, prosecuted, convicted or punished for [certain] humanitarian acts.”). According to the ICRC, concerning the provision in AP I, “[t]he obligation to refrain from punishing is addressed to all authorities in a position to administer punishment, from the immediate superior in the hierarchy of the person concerned who is entitled to do so, to the supreme court of a State.” ICRC, Commentary on the APs, para. 651 [italics added]. That obligation to refrain from punishing entailed in article 16(1) AP I purportedly “applies not only to the enemy authorities, but also to the authorities of the State of which the person concerned is a national. This is important, because there could be a great temptation for a State to punish its own nationals who have administered care to the enemy wounded.” Id. Pursuant to the ICRC’s analysis, falling within the ambit of these protections under article 10(1) AP II would include not only doctors but also, among others, “nurses, midwives, pharmacists and medical students who have not yet qualified.” ICRC, Commentary on the APs, para. 4686. See also International Committee of the Red Cross, Draft Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949: Commentary, October 1973, Geneva, p. 148 (stating that “[t]his rule is the corollary of the principle whereby the wounded and the sick shall be entitled to the care necessitated by their condition […]. It concerns any person exercising a medical activity, whether doctor, dentist, nurse or stretcher-bearer; whether a member of the medical personnel as defined in [a draft article that was ultimately not include in AP II] or persons exercising such an activity, although not attached to a medical unit of a party to the conflict.”) [italics added]. Further, according to the ICRC Commentary on the relevant provision in AP II, “[t]he reference to punishing is meant to cover all forms of sanction, including both penal and administrative measures.” ICRC, Commentary on the APs, para. 4691. And, again according to the ICRC Commentary, “[t]he term ‘medical activities’ should be interpreted very broadly. The concept is broader than that of medical care and treatment. A doctor not only treats patients, he may also be called upon to issue death certificates, vaccinate people, make diagnoses, give advice[,] etc.” Id. at para. 4687 [internal citations omitted].

[113] Today, the IHRL principle of legality may help shield caregivers from the abuse of unlawfully ambiguous definitions of terrorism-related offenses. See, e.g., De La Cruz-Flores v. Peru, Merits, Reparations, and Costs, Judgment, Inter-Am. Ct. H.R. (ser. C) No. 115, para. 102 (Nov. 18, 2004) [hereinafter IACtHR, De La Cruz-Flores v. Peru]; see also id. at para. 188(1).

[114] ICRC, CIHLS, Vol. II: Practice, Part 1, pp. 486–492.

[115] Article 10(1) AP II is one of the few provisions of the Protocol that the Manual does not expressly incorporate. While the Manual does not expressly prescribe criminal punishment for those who provide medical care to the enemy in NIAC, it also does not prohibit such punishment. Moreover, the Manual does reference the capacity of the state to sentence those who “support” enemy non-state armed groups to a variety of offenses, including “material support to terrorism or terrorist organizations.” U.S. Department of Defense, Law of War Manual § 17.17.1.2 (2015). Under U.S. law, that offense includes the provision of certain medically related activities (except medicine itself)—such as “expert advice or assistance”—to terrorist organizations. See infra Section 5: “Domestic Proceedings against Medical Caregivers — United States of America.” The reasoning for the lack of inclusion of the protection against punishment laid down in AP II is left unstated in the Manual. The Manual notes in a different section that, over all, “[a]lthough the [United States] is not a Party to AP II, reviews have concluded that the provisions of AP II are consistent with U.S. practice, and that any issues could be addressed with reservations, understandings, and declarations.” Id. at § 19.20.2.1 [citations omitted]. None of the referenced reservations, understandings, or declarations would, however, limit the scope of protection under article 10(1) AP II. Indeed, the only relevant reservation concerning article 10(1) AP I is found in an analysis attached to the letter transmitting AP II to the Senate for ratification, which states that “[a] reservation to this Article is necessary to preserve the ability of the U.S. Armed Forces to control the actions of their medical personnel, who might otherwise feel entitled to invoke these provisions to disregard, under the guise of ‘medical ethics’, the priorities and restrictions established by higher authority.” Detailed Analysis of Provisions, Attachment 1 to George P. Shultz, Letter of Submittal, December 13, 1986, Message from the President Transmitting AP II, p. 5 [italics added].

[116] Articles 12 GC I, 12 GC II, 13 GC III, 32 GC IV, 11(2) AP I, and 5(2)(e) AP II.

[117] The exact contours of the protection are formulated slightly differently between the Protocols: compare article 16(2) AP I with 10(2) AP II. See also International Institute of Humanitarian Law, The Manual on the Law of Non-International Armed Conflict with Commentary para. 3.2.b (2006) (“Medical […] personnel must not be required to perform tasks other than appropriate medical […] duties. They must be given all available assistance when performing their duties.”).

[118] Articles 16(2) AP I and 9 and 10(2) AP II.

[119] According to the ICRC’s Commentary on the APs, “[t]he use of the verb ‘to compel’, taken from [article 33 GC III], refers to cases where medical […] personnel have fallen into the hands of the adversary. In addition to being protected by [article 5 AP II], like any other persons deprived of their liberty for reasons related to the conflict, they are also granted the guarantee of not being compelled to carry out tasks which are incompatible with their mission.” ICRC, Commentary on the APs, para. 4676 [internal citations omitted]. The Commentary elaborates that

[t]his could refer to medical experiments, but also […] to camouflaging military operations under cover of medical tasks. The second possibility may materialize not only when medical or religious personnel have fallen into the hands of the adversary: the parties to the conflict may in no case compel the personnel in question to carry out military tasks as these are, by their very nature, incompatible with any humanitarian mission; medical assignment must be exclusive.”

Id.

[120] See generally Sigrid Mehring, First Do No Harm: Medical Ethics in International Humanitarian Law 133–175 (2015).

[121] See, e.g., Section 3: “Related Fields of International Law — International human rights law.” IHRL also provides an independent basis for the IHL protections against torture, against cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, and against being subjected without one’s free consent to medical or scientific experimentation. Articles 7 and 4(2) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, December 16, 1966, 999 U.N.T.S. 171 (ICCPR). None of those rights may be derogated from.

[122] ICRC, CIHLS, Vol. I: Rules, Rule 26, pp. 86–87.

[123] ICRC, CIHLS, Vol. II: Practice (Part 1), pp. 486–97. See the discussion and corresponding citations infra Section 3: “Customary IHL — ICRC’s Customary IHL Study.”

[124] Breitegger, “The legal framework,” supra note 32, at p. 119 [citation omitted]. With respect to the issue of non-denunciation, medical ethics are said to be in tension with IHL. Id. Non-denunciation implicates not only medical confidentiality in particular but also medical ethics more generally. Medical confidentiality in this context refers as a general rule “to the discretion that a doctor must observe with respect to third parties regarding the state of health of his patients and the treatment he has administered or prescribed for them.” ICRC, Commentary on the APs, para. 670 fn 21 (referring to CE/7b, p. 22) [italics added]. Medical ethics “generally require absolute confidentiality with regard to the patient’s identity and other personal information as well as health-related information […].” Breitegger, “The legal framework,” supra note 32, at p. 119 [citation omitted]. In general, that absolute confidentiality is “subject to the […] discretion of health-care personnel when there is a real and imminent threat to the patient or others and this threat can only be removed by breaching confidentiality.” Id. at pp. 119–120 [citation omitted; italics added].

[125] ICRC, Commentary on the APs, paras. 670–675.

[126] Id. at para. 671.

[127] See ICRC, Commentary on the APs, paras. 670–74.

[128] For many delegates at the Diplomatic Conference, the protection due to those engaged in medical activities in NIACs raised threshold questions regarding state sovereignty, especially the power to compel information about those who have engaged in unlawful activities. Some delegates favored deleting the entire article or certain of its paragraphs. See, e.g., in CDDH/II/SR.28, the statements of the delegations of Canada, Mr. Marriot, p. 283, para. 14; of Australia, Mr. Clark, p. 283, para. 17; and of Indonesia, Mr. Ijas, p. 283, para. 19. Others were adamant that the non-denunciation protections had to remain, with a delegate of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.), for example, emphasizing that the draft provisions concerning compelling information “raised a point of crucial importance, which would indicate just how far the Conference was prepared to go in extending the humanitarian law applicable to any type of armed conflict.” CDDH/II/SR.28, Mr. Krasnopeev, U.S.S.R., p. 284, para. 25 (and further stating that “[i]t had already been agreed that a rule of that type was appropriate in the case of international conflicts; it was impossible to argue that the same provision, in the case of internal conflicts, constituted a violation of national sovereignty, or were there any grounds for saying that the paragraph would be inapplicable in the case of an internal conflict.”). Id. at pp. 284–85, para. 25. See also, e.g., in CDDH/II/SR.28, the statements of the delegations of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Mr. Denisov (stating that “he could not agree that paragraph 3 should be deleted. It had nothing to do with sovereignty; it was a question of providing protection to medical personnel in the case of an internal conflict. To delete the paragraph would seriously weaken the impact of the whole Protocol.”), p. 284, para. 22; of Iraq, Mr. Al-Fallouji (stating that “[t]he real question was how far the international community was ready to go in humanizing such conflicts. He thought it was prepared to make some advance, but it should not be pushed too far. The present Conference was useful precisely because it helped to reveal the degree of maturity of international opinion.”), p. 285, para. 29.

A working group was established to consider the provisions regarding compelling information. See, e.g., O.R. Vol. XI, CDDH/II/SR.41, pp. 447–456. During the discussion, Mr. Krasnopeev, of the U.S.S.R. delegation, stated that “[i]t was […] clearly necessary also in the case of an internal conflict to protect medical personnel against abusive external pressure and to allow the doctor himself to decide if he should act as a doctor or as a participant in the armed conflict.” O.R. Vol. XI, CDDH/II/SR.40, p. 424, para. 31. Mr. Krasnopeev also stated that according to the proposal under review an obligation for doctors to give information concerning their suspicions “would be valid in an armed internal conflict not only in cases of common law crimes but also in the case of political crimes, since every government considered those who had sided against it as political criminals. Many historic cases could be cited of individuals regarded by the authorities of former days as dangerous political criminals who had afterwards become Heads of State. That had even occurred many times in the case of Napoleon.” Id.

[129] See Articles 16(3) AP I and 10(4) AP II. The AP I provision is also subject to the requirement that “[r]egulations for the compulsory notification of communicable diseases shall [...] be respected.” Id.

[130] See ICRC, Commentary on the APs, para. 684 (stating that “there is no obligation upon those exercising medical activities to remain silent. They may denounce the presence of the wounded to the authorities even when they know that this will be prejudicial to the wounded person or his family, if such denunciation is in their view necessary for saving lives. The prohibition is aimed at those who could compel such denunciations.”) [italics added].

[131] See ICRC, Commentary on the APs, paras. 686–88.

[132] See, e.g., ICRC, Commentary on the APs, para. 688. Conforming that view with respect to the “subject to national law” condition in AP II, United Kingdom Ministry of Defence, Joint Service Publication 383, The Joint Service Manual of the Law of Armed Conflict para. 15.46.b fn. 108 (2004) (also explaining that “the final text was a compromise to avoid a perceived violation of the principle of non-interference with the internal affairs of states”).